Effects of top scavenger declines—from microbes to ecosystems

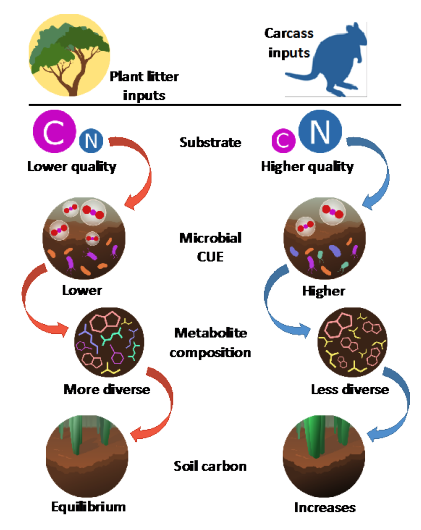

Conceptual model linking resource quality with soil carbon persistence.

Unless first consumed by a predator, all animals enter the carrion pool when they die. Scavengers and microorganisms play a critical role in returning carcass-derived nutrients to the soil where they get recycled and used for plant uptake and growth. The impact of carrion inputs on nutrient cycling, food web dynamics, and ecosystem carbon balance remains a mystery. With global declines of many species including scavengers, it is essential to quantify how the quantity and quality of carrion-derived nutrients shapes plant community structure and ecosystem dynamics. Tasmanian devils are an ideal and charismatic species with which to study the effects of scavenging on ecosystem processes. They are one of a few carnivores worldwide that consume bones. By accelerating the cycling of key plant growth-limiting nutrients that would otherwise remain locked in bone material for years, Tasmanian devils provide a critical ecosystem function. In recent years, the emergence of a highly transmissible cancer — devil facial tumor disease, or DFTD — has dramatically reduced devil population sizes in eastern Tasmania and has spread throughout the island, threatening this iconic species with extinction. Researchers will use this tragic situation to test whether devil-scavenging impacts can be detected on an ecosystem scale and how devil population declines result in a shift in the role of other scavenger species.

This research is supported by the National Science Foundation award 2054716.